Essay

Brian LaRossa’s provocative exhibition celebrates designers who defy the norms of their profession and who also make objects that we call “art.” Keetra Dean Dixon’s piece, A-Way, is a nylon flag that zips apart from itself. It opens its fly and comes undone. Dixon’s materials beckon from the world of useful things, but her piece refuses to be utilitarian. It illuminates language rather than using it to promote or persuade. It hangs on a wall in a gallery, not on the sale rack at Kohl’s. Dixon’s misbehaving artifact has no client. It solves no problem and sells no product—except for perhaps itself.

Whenever I see the word “undefined,” I start hunting for definitions. Those for the terms “design” and “art” are notoriously difficult to pin down. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, the esteemed cultural authority for whom I have toiled for over twenty years, accepts numerous working definitions of design. Rather than pick one, Cooper-Hewitt’s curators and museum educators buzz around a swarm of colliding notions. Sometimes we focus on process: design as thinking, design as making, or design as decoration. Sometimes we focus on people: design for users, design for clients, design for social change, or design for designers.

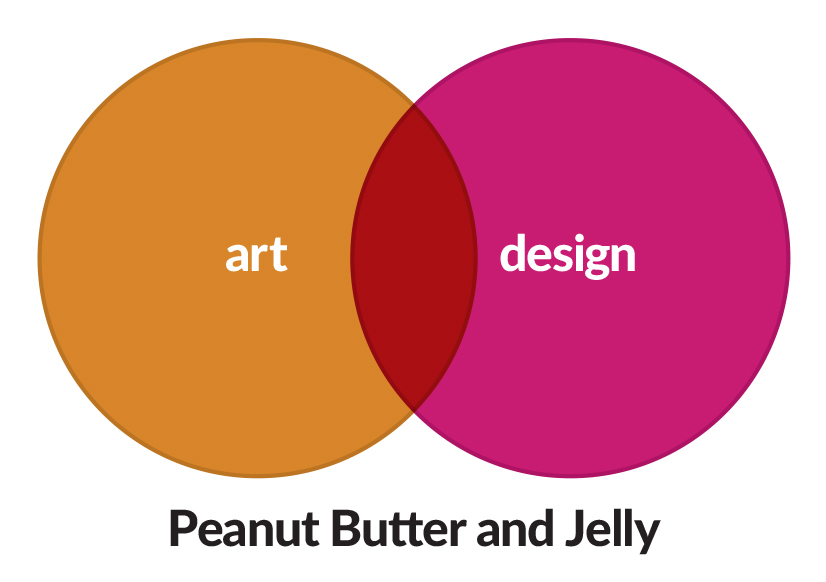

Since defining design is so difficult, and LaRossa’s exhibition is about how design and art overlap, I decided to think about the overlap. How does design exist in relation to art? Surely the handiest tool for thinking about overlaps is the Venn diagram. This bubble-shaped wonder of the philosophical imagination helps us understand categories of objects or ideas in relation to one another. What do categories include and exclude? How do we come to understand things by seeing what they are not?

Imagine the work in LaRossa’s show stuck in the middle of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, right at the plane where the sweet-and-sour personality of fruit preserves confronts the dense, chalky heaviness of pulverized peanuts. Elliott Earls’s work occupies a sticky frontier where two antagonistic substances meet. Think of jelly as graphic design; it’s popular, accessible, and communicates a message. Peanut butter, on the other hand, is art; it’s serious, obscure, and hides its meaning at the back of your throat. Debbie Millman’s white-on-white visual poem is a wonderful piece of PBJ. Her bright narrative voice and inviting typography provide the jelly while the opaque monochrome surface brings on the peanut butter, supplying gravitas and a welcome layer of discomfort. Like peanut butter, art makes you work a little harder.

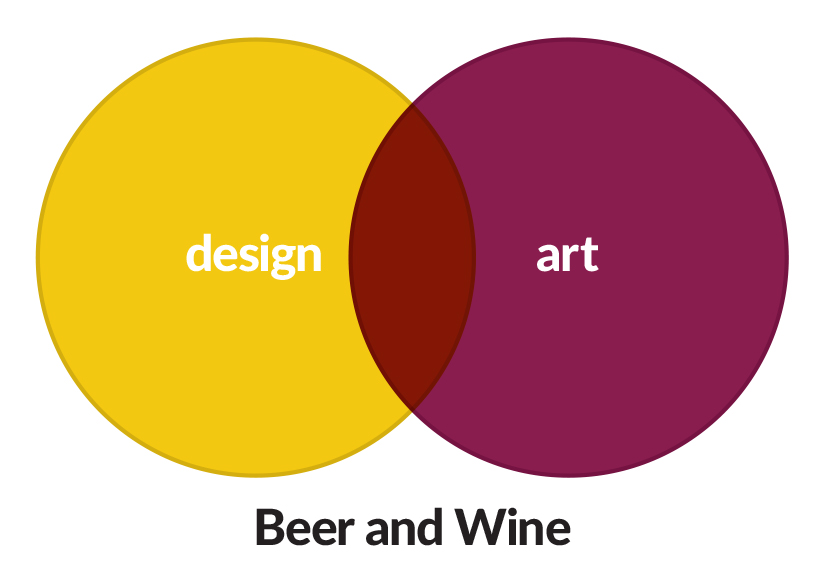

My next diagram gets at the culture clash between design and art. Wine, like art, has a reputation for classiness while beer is the working man’s drink. (Needless to say, there is plenty of cheap wine and bad art in modern society, and beer is now a collector’s item in certain parts of Brooklyn.) When you mix highbrow and lowbrow together, you get a toxic brew indeed: middle brow. Luckily, nothing in LaRossa’s show tastes quite like Weer or Bine, but the danger is always there. (Don’t you cringe when design tries too hard to be art?)

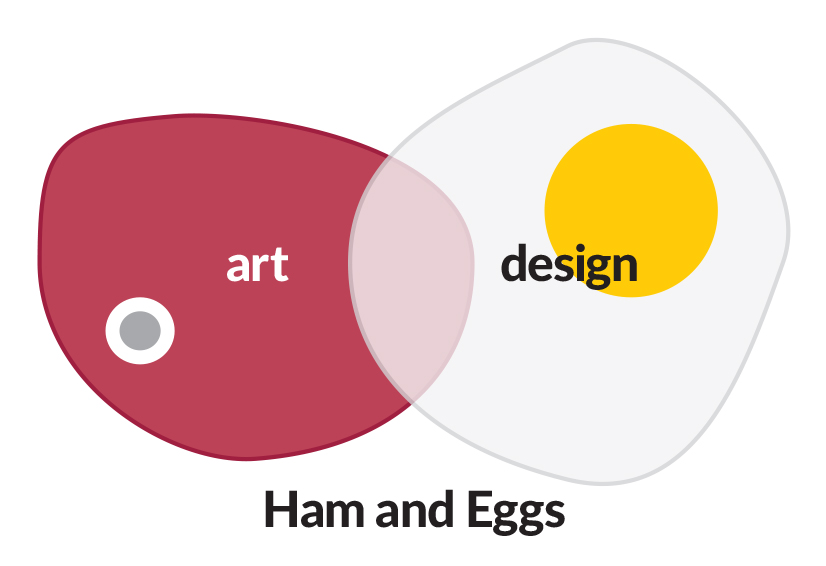

Maybe my first two diagrams are too simple. They don’t reveal the secrets that design and art are trying to keep from each other. Consider ham and eggs. Ham is art; it’s an expensive product that has been cured by salt, sugar, or fire to endure the test of time. Eggs are design; they are a cheaper form of sustenance that shouldn’t linger in your fridge for more than a week or two. Although ham and eggs each have their own discourse and history, creative people have been cutting them up and mashing them together for centuries. But ham harbors something that is hard to penetrate—even by its own insiders. It’s the art market, that marrow-rich bone of late capitalism with the power to create value that exceeds utility.

Like artists, designers have their own way of doing business, but theirs is rather obvious and accessible. Designers make contracts with clients and users in order to create stuff that people need or want. The rewards of these contracts are smaller but more reliable than the rewards locked away in art’s magical ham bone.

Many of the pieces shown in Undefined by Design are for sale; some of them aren’t. The gallery creates a context where people can experience various artifacts as autonomous objects of contemplation as well as players in a special kind of commerce, one that is usually closed to graphic design. Brian LaRossa has bravely collected a disparate roster of things into a space where we can value them in new ways.